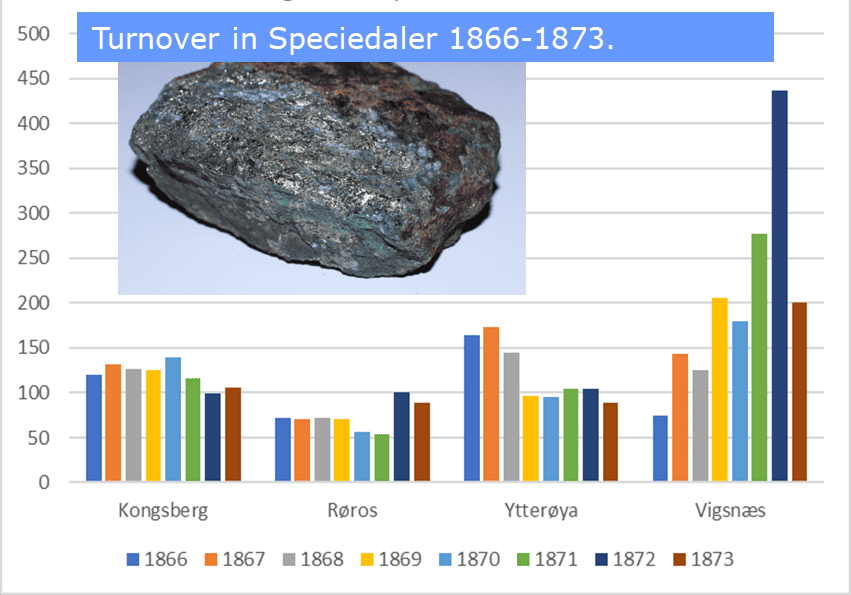

In the 1870s and into the 1880s the copper and pyrite mine at Vigsnæs in Avaldsnes on the west coast island of Karmøy was the largest mine in Norway. For more than a decade the newcomer, now known as Visnes or Vigsnes, on the North Sea surpassed the 300-year-old Royal silver mining establishment at Kongsberg Sølvværk in eastern Norway, as well as the 200-year-old highland copper works at Røros Copper Mine. The mine at Vigsnes was foreign owned, imported modern technology and capital from Europe and did very well right from the start in 1865.

In the beginning of the 1890s mining engineers and management knew the Vigsnes mine would soon be empty of ore if new discoveries were not made soon. The mine was closed at the end of 1894. Some of the workers would have to depend on poor relief. But many saw the writing on the wall before the mine closed and moved to other mines in Norway, especially in Northern Norway. Some went to the Røros mine in central Norway or to the new mine opening in Sulitjelma in northern Norway. A remarkable number, however, emigrated to the US and got work in Montana.

The Norwegian Census of 1910 registered return migrants for the first time, gathering new data about the so-called Norwegian-Americans. The author has located every person in the census listed as a return migrant in all municipalities on the island of Karmøy, the year they emigrated, the year they returned to Norway, and the last place they worked in the US before returning to Karmøy municipalities. This surprisingly fresh knowledge gives us interesting new insights in what happened to the miners at Vigsnes, about transfer of mining technology and mining knowledge and about the interchange that occurred internationally in the mining industry.

It is hardly surprising that men who grew up on the Karmøy island and emigrated to the US found work related to shipping and fisheries in the US, both on the East and the West Coast, or that young women had worked as maids. This was also to a large degree the case in 1910 for the Norwegian-Americans living in Avaldsnes municipality, where the Vigsnæs mine was located. Nevertheless, what really looms large for Norwegian-Americans living in Avaldsnes, compared with all the other municipalities on Karmøy island, is how many return migrants had lived in Montana. It was the leading copper producing state in the US around 1900.

The state of Michigan had been the leading copper state since 1845. From the late 1870s large volumes of copper was also produced in the state of Arizona. Copper production increased fast in the 1880s, and in 1887 Montana passed Michigan as the largest producer in the country. Montana held the position as the largest copper producing state for more than two decades.[1] Most of the men in the Avaldsnes records registered as their last workplace a “Copper smelter” or work in a mine in Great Falls, Anaconda or Butte.

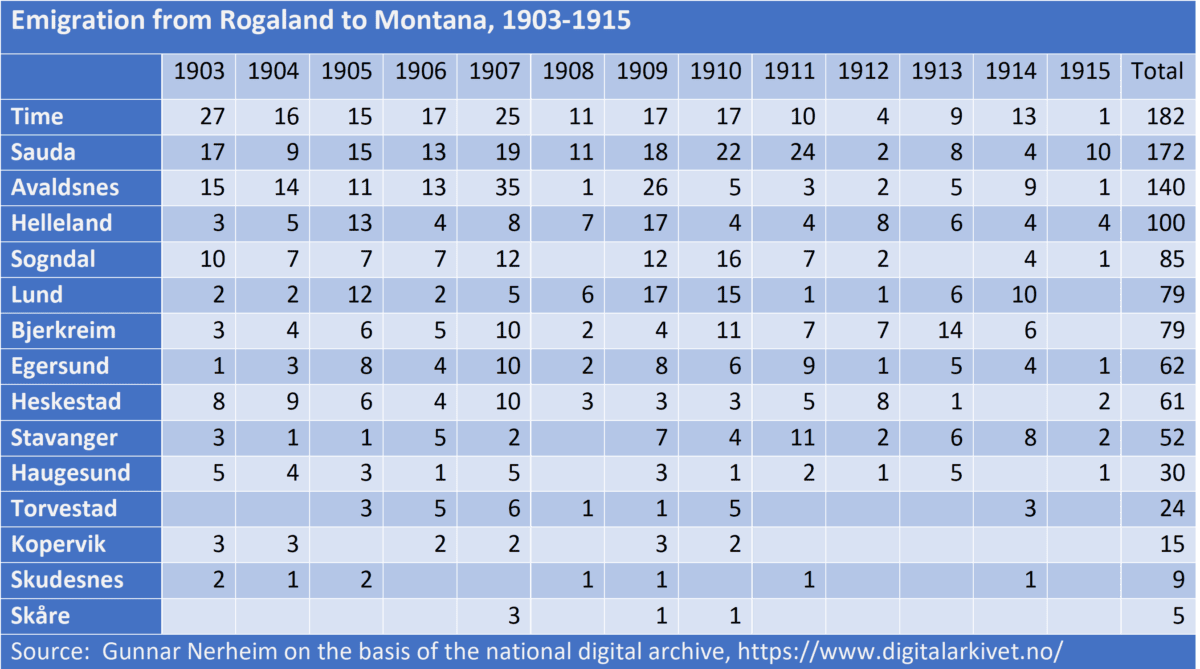

Between 1903 and 1915 many young men from all over Rogaland County, Norway, found the state of Montana to be an attractive goal. Every spring, men and a few women left for Montana from the agrarian municipalities in the lowland region of Jæren and the hilly dales of Dalane in Rogaland. The highest number of persons during the period emigrated from the municipalities of Time, Sauda and Avaldsnes. Most of these immigrants to Montana found work in agriculture and the livestock business. Many young men from municipalities like Time, Sauda, Heskestad, Helleland, Lund and Egersund worked as «faarehyrde» (sheep herder). Compared with the rest of the municipalities in Rogaland, immigrants from Avaldsnes were exceptional. Not a single person among the return migrants from Montana to Avaldsnes had worked as sheep herder or on a farm.

Immigrants from Avaldsnes to Montana often chose to work in the mines. The activities in the Vigsnes mine in the 1870s and 1880s were as in most mining communities intertwined with all sectors of local life. Evidently a tradition for mine work as a normal way of life had slowly developed in the municipality of Avaldsnes. Men and teenagers knew more money could be earned in the mines than by doing agricultural work, both in Norway and the US. Many among the men who emigrated after 1900, had in fact been too young to work in the Vigsnæs mine. But they had fathers and uncles and people they knew well who had worked in the mine. Looking for work in Montana, they sought out mining related jobs, despite the higher risk and an unhealthy environment.

A couple of Norwegian engineers who had worked in the Vigsnes mine also emigrated to Montana. One of them was the young mining engineer H. K. Borchgrevink, who got his first job as an engineer at Vigsnes in 1892. After the mine closed, he travelled to Montana and got work at Anaconda. He returned to Norway in 1899.[2] Several others from Vigsnes followed this migration pattern. They worked for a couple of years in Montana, returned to Norway, went back to Montana again etc. Among the return migrants to Avaldsnes in 1910, several got jobs in the new Vigsnes mine.

Chain migration from municipalities in Rogaland County

It is easy to spot chain migration to specific counties in Montana, but harder to reconstruct the steps and interrelationships that made up the chains. Through series of individual migrations, often in a relatively short period of time, the ethnic culture of a group in a country or region in Europe was transferred to specific places in a city or rural area in the United States. Whole systems of chain migration “operated like a transmission belt that brings newcomers from one area to a particular location,” according to Robert Ostergren.[3]

Relatives from the same region followed in the footsteps of each other at different times and ended up in the same place in the USA. Salary and prospects for the future were important, but it was at least as important not to need to cut every tie and leave behind everything that was familiar and dear from the place where they grew up.[4] Emigrants from Rogaland County to Montana in the period 1903-1915 were fully aware of where relatives or people from the same place in Norway had settled in Montana. They did not enter a totally unknown world.

In the Norwegian 1910 census names of inhabitants in Avaldsnes municipality were still listed as living in the USA, but since they had lived there only a short time, the parents still expected them to return. Very few return migrants to Rogaland County had worked in the copper industry in Butte, Anaconda or Great Falls. On the list of return migrants to Avaldsnes, however, a surprising number of persons had worked in the Montana mining industry. Some of them had also worked in copper mines in Arizona, Utah, and Mexico.

The number of emigrants from Avaldsnes municipality to Montana increased in the 1880s

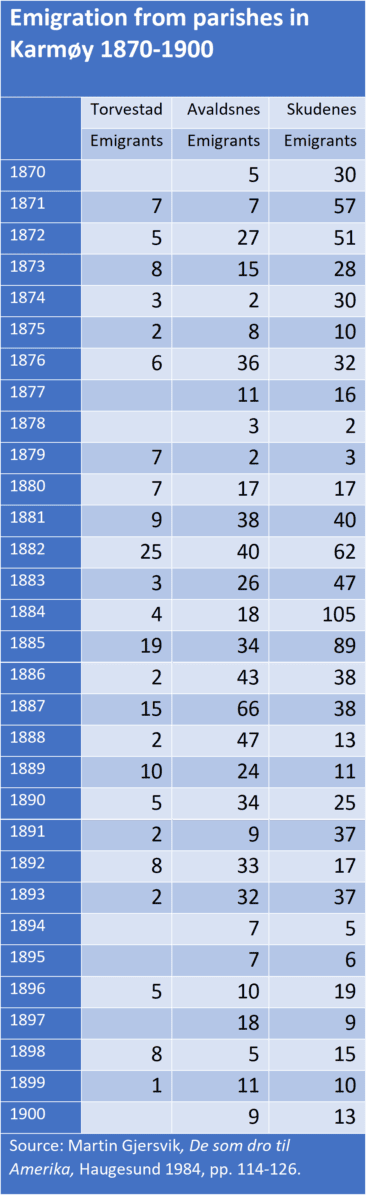

The rich spring herring fisheries had constituted the backbone of economic life for people on the Karmøy island for decades from the beginning of the 19th century. When the herring dissappeared in the 1870s, a new pattern of population movement emerged. In this period, people had moved from other places in Norway to Karmøy to get work. In the 1880s and 1890s the tide turned, and people left Karmøy municipalities.

Emigration became a new fact of life. Some emigrated and never returned. But soon many only went away during certain months when work was easier to get in the US and returned to Karmøy when the season in America was over.

Inhabitants of Karmøy became return migrants. In his book De som dro fra Karmøy til Amerika, the author Martin Gjersvik listed names and families of a number of emigrants to the USA from Torvestad prestegjeld, Avaldsnes prestegjeld, and Skudenes prestegjeld.[5] The largest emigration decade was the 1880s, and Skudenes prestegjeld counted the largest number of emigrants

The list of return migrants in 1910 also included a number of persons from Skudenes who had worked as seamen and fishermen in the US, the same type of work they had grown up with in Norway. Among the return migrants to Avaldsnes many Norwegian-Americans had been engaged in this type of work as well, but the number of men who had been working in mining dominated. In the 1880s it was not evident that the Vigsnes mine would close in the future.

Some return migrants in the 1880s

Among the emigrants in the 1880s was 26-year-old Svend Eriksen. In 1910 he had returned, had acquired the farm Røgsund Myren, farm number 84/, and also worked as a carpenter. He was born at Avaldsnes on April 12, 1861, and emigrated to the US in 1887. Before Svend Eriksen returned in 1893, he had worked at a copper smelter in Great Falls, Montana. He had obviously earned enough money in Montana to marry and buy his own farm after his return to Norway.

Peder Baarsen, born at Avaldsnes on April 29, 1861 emigrated in 1888 and returned in 1893. In 1910 he owned his own farm Myklebostad, farm number 80/2. His last workplace in the US before his return was a gold washery at Marysville, Montana. The gold mine was located 60 km northwest of the state capital Helena. His wife, born Ingeborg Knutsen in the Norwegian silver city Kongsberg on November 19, 1858, had emigrated to the US in 1884 and returned in 1890. She was pregnant when she returned and settled in the municipality of her husband, Avaldsnes. Their daughter Petra Pedersdatter was born in Avaldsnes on December 8, 1891.

Gunnar Torsen was registered as living on his own farm Kalstø, farm number 18/1, and was also a fisherman. He was born May 30, 1864, at Avaldsnes. Gunnar emigrated in 1883 at the age of 19, and returned in 1895. His last place of work in Montana before his return to Norway was at a gold washing plant in Montana.

Knut Vilhelmsen, born Avaldsnes July 22, 1860, lived on the farm Velde south, farm number 29/4, in 1910. He owned the farm and was also the foreman on an icing plant for herring. Knut emigrated to the US in 1888 and returned to Norway in 1894. His last workplace before his return was at a copper smelter in Great Falls, Montana.

On Austevik, farm number 39/5, lived the farmer Hans Hansen. He also worked as a carpenter. He was born on January 7, 1851, emigrated to the US in 1887, and returned to Norway in 1891. His last working place in Montana before his return was at a copper smelter in Great Falls, Montana. In 1910 his son Helmer Hansen, born Avaldsnes on July 27, 1884, had worked three years at a mine in Anaconda, Montana. His younger son Osmund Hansen, born Avaldsnes on January 10, 1888, had participated in salmonfishing in Washington for three years.

The son Tomas Thorsen on Hørdal Vormedal, farm number 27/6, had emigrated to the US. He was born on May 9, 1877, and in 1910 he worked at a copper smelter in Montana. His sister Joseffine Thorsen, born May 15, 1883, had emigrated as well. She worked as a housemaid in New York.

Sven Svensen lived on the farm Kolstø, farm number 34/4. His main occupation was fishing. He was born in Avaldsnes on September 29, 1855, and emigrated in 1886. After 16 years in the USA, he returned to Norway in 1902. His last workplace was at a copper smelter in Great Falls. His wife Inger Svensen was born at Avaldsnes on May 17, 1860. She emigrated in 1888 and returned in 1892. Her last position in the US before her return was as a housemaid in Illinois.

On Kolstø, farm number 34/7, lived the farmer Aksel Baardsen, who was married. He was born on August 18,1850, and emigrated in 1882. Ten years later, in 1892, he returned to Avaldsnes. His last workplace in Montana was in a silver mine. His wife Karen Baardsen was born at Lom, Gudbrandsdalen, on January 14, 1858. She emigrated in 1881 and returned from Montana in 1892. Their foster son Magnus Gabrielsen was unmarried. He was born at Avaldsnes on May 1, 1889, and in 1910 he had worked two years on the railroad at Great Falls, Montana.

On the farm Kolstø Neset, farm number 34/15,2, lived Ole Einarsen. He was born on March 21, 1865, and emigrated in 1887. Before his return to Norway in 1898, he worked at a silver mine at Elkhorn, Montana, south of Helena.

Peder Olai Monsen lived on the farm Rygge, farm number 33/1,2, and was also a carpenter. He was born on January 25, 1859, at Avaldsnes. In 1910 he worked in New York. His wife Marta Kristine Johannesdatter, born August 22, 1862 at Avaldsnes was a Norwegian-American. She emigrated in 1887 and returned in 1890. Her last workplace in the US was as a maid in Montana. Their daughter Helene Pedersdatter was born in Montana on July 28, 1889. Their son Bernard Pedersen was born on October 28, 1890, in Montana. In 1910 he still lived in Montana and had worked in Great Falls for two years.

On Matland, 32/2, lived the farmer Sven Sørensen, born Avaldsnes on March 30, 1863. He emigrated in 1885 and returned to Norway in 1893. His last place of work was at a smelter in Great Falls, Montana. Their son Aanen Svensen, born at Avaldsnes on November 14, 1891, was still unmarried in 1910. He had worked 18 months at Great Falls, Montana, the same town where his father had worked.

Aksel Widwey was registered as a farmer at Matland, farm number 32/4. He was born at Sand, Rogaland County, on October 7, 1870, and emigrated in 1888. Aksel returned to Norway in 1907. His last working place in the US before his return was at a copper smelter in Great Falls, Montana.

Mathias Thuestad worked in Mexico

The person who had worked farthest away from Avaldsnes, was the Norwegian-American Mathias Thuestad. In 1910 he lived on the farm Røgsund Nydalen, Farm number 84/11. He was born at Avaldsnes on December 6, 1864, emigrated in 1886, and returned in 1894. His last job before his return to Norway was as foreman at the copper smelter in Aguascalientes, Mexico.

The Guggenheims were the owners of this mine. In 1889 Simon Guggenheim persuaded some Mexican mine-owners to ship their silver ore to a Guggenheim-smelter at Pueblo, Colorado. After Congress introduced high customs on imported silver ore, Guggenheim built its own silver refinery in Monterrey and Aguascalientes. Guggenheim first rented the rights to do silver mining in Mexico, but soon bought the mines. In 1901 Guggenheim produced 40 per cent of all lead and 20 per cent of all silver in Mexico. When Mathias Thuestad returned home to Avaldsnes he had many exotic stories to tell his neighbours from his life in mining in the US and Mexico.

Photo credits: Visnes Gruvemuseum, Karmøy, visnes.gruvemuseum@gmail.com.

Statue of Liberty miniature: Inger Kari Nerheim.

Graphs: Gunnar Nerheim

Specimen as graph illustration of rich copper ore comes from the original mine, Gammelgruva. CuS, courtesy of Aleksander Hauge. In its purest form it could contain 32,3 per cent Cu.

[1] F. E. Richter, “The Copper Mining Industry in the United States, 1845-1925”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Feb. 1927, vol. 41, pp. 236-291.

[2] «Bergverksdriften i 1938», Tidsskrift for Kjemi og Bergvesen, nr. 1, 1939, p. 15.

[3]Robert C. Ostergren, A Community Transplanted. The Trans-Atlantic Experience of a Swedish Immigrant Settlement in the Upper Middle West, 1835-1915 (Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988), p. 8.

[4] Marjory Harper, Adventurers & Exiles. The Great Scottish Exodus, London 2004, pp. 106-107.

[5] Martin Gjersvik, De som dro fra Karmøy til Amerika, Haugesund 1984.