Many people have written about the history of the Montana cattle industry. In comparison, historical research and writing on the sheep industry in Montana is scant. The stories of “the great sheep trails from California and Oregon have lain in deep obscurity,” wrote Edward N. Wentworth in 1941, while the trails from Texas “with its cowboys and longhorns” have been given a lot of attention. According to Wentworth “the rush of their hooves fully equaled that of their more widely advertised cattle drives.”[1] K. Ross Toole agreed, “myth and fact are so interwoven in Montana’s history, mention is seldom made of sheep in the books which presume to tell us about our past. Yet at one time Montana raised more sheep and produced more wool than any other state in the country.”[2]

When was the sheep business introduced in Montana?

Most writers agree that it was the rich gold discoveries in Montana in 1862 and 1863 that led to the development of sheep ranching.[3] Livestock entrepreneurs drove sheep from California and Oregon to Montana to sell them as mutton in the digging camps. “In contrast to some other places, like Wyoming,” wrote Michael P. Malone and Richard B. Roeder, “breeders of sheep and horses got along reasonably well with cattlemen in Montana; many operators in fact, raised horses, sheep, and cattle together.”[4]

The breakthrough for sheep ranching in Montana came in the 1870s. In 1866 the Far West contributed only 15 per cent of the wool clip in the United States, which increased to 25 per cent of the wool clip in 1873, and about 45 per cent in 1885. The increase in the number of sheep in the far West after 1890 was almost entirely the result of the concentration of the sheep industry in the Rocky Mountain region, and especially Montana.

Where did the sheep come from?

Around 1880 the greater part of the sheep in Montana came from Oregon and the Northwest. Hundreds of thousands of yearling ewes crossed the trails from California and Oregon into Montana. Wethers constituted the bulk of the sheep drives, not least because it was more complicated to trail ewes and lambs than wethers. Most of the pioneer trail bands from California had their origin in the large Mexican-Spanish flocks that had been moved into California on the heels of the gold seekers.[5]

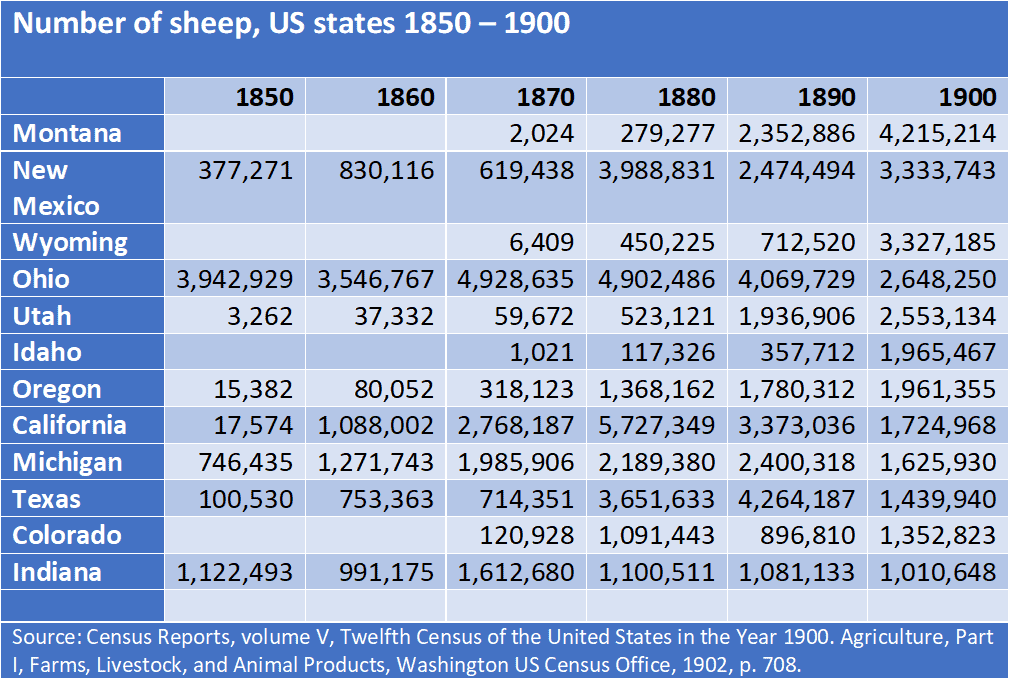

Between 1877 and 1880 as many as 350,000 sheep were exported from California to states in the east, including Montana. Sheep from Oregon, however, proved to adapt easier to the Montana environment than sheep from California. In 1883 the US Department of Agriculture estimated that 600,000 head of cattle and 500,000 head of sheep grazed in Montana. Sheep ranching grew almost as fast as cattle ranching.

Montana was the leading sheep state in the United States in 1900

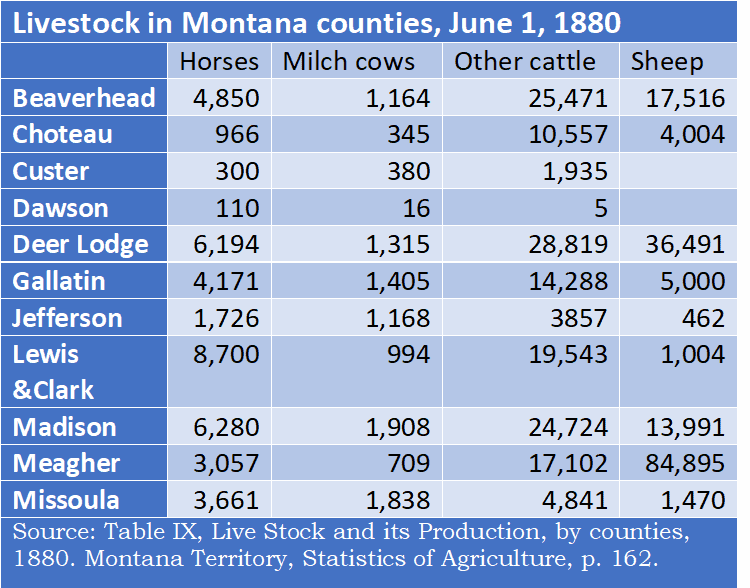

The sheep population in Montana increased from 2,024 in 1870 to 270,277 in 1880 and 2,352,886 in 1890. In the western United States only California had more sheep. To most people it is surprising that Texas in 1890 was the state with the highest number of sheep in the United States: a total of 4,264,187. Ten years later the sheep population in Texas had fallen to 1,439,940.

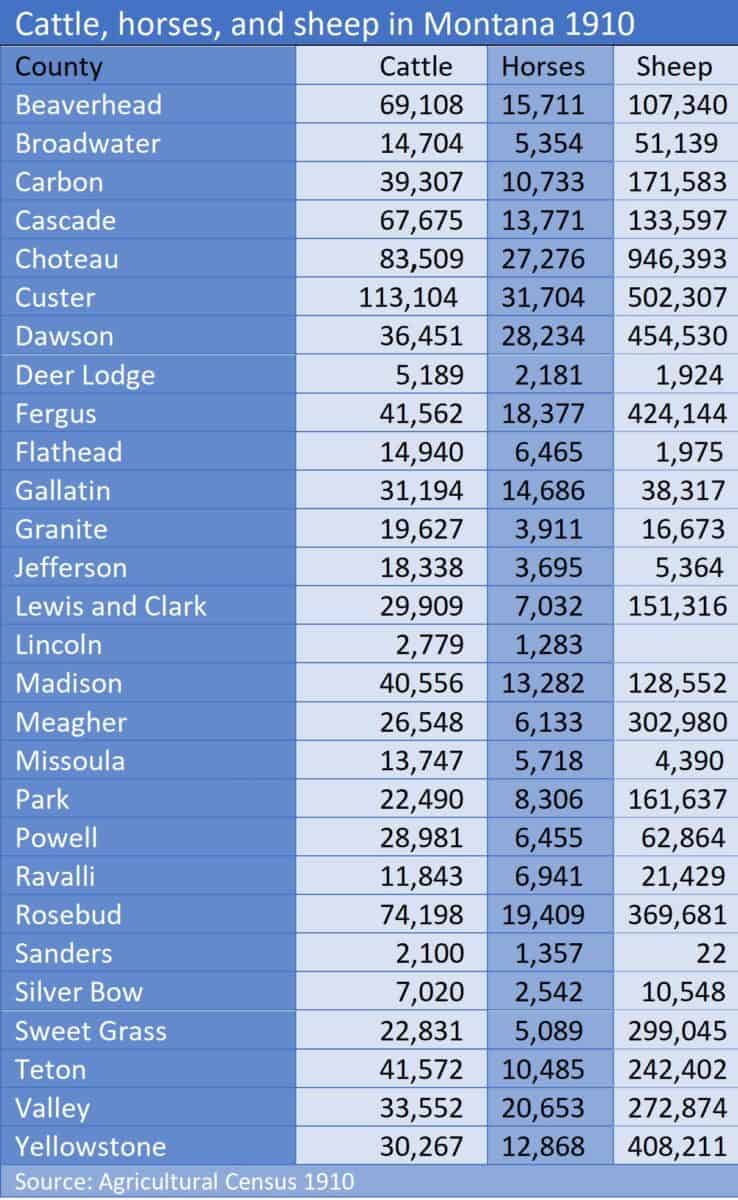

Montana had 4,215,214 sheep in 1900, and sheep husbandry peaked in 1909 with 6,643,000 sheep. At the same time dry land farmers arrived in large numbers with consequences for the free ranging sheep and cattle ranchers, who had to reduce the number of cattle and sheep considerably on the land they used. In 1921 the number of sheep in Montana had decreased to two million and continued to decline, not least because of higher cattle prices.

Choteau County was the leading sheep county in Montana in 1910, with 946,393 sheep followed by Custer County with 502,307, Dawson with 454,530, Fergus with 424,144, Yellowstone with 408,211, Rosebud with 369,681, and Meagher with 302,980.

The emerging sheep industry

The Montana Woolgrowers established their own Association in Fort Benton in January 1883. The hard winter of 1886/1887 did not hurt the sheep industry to the same degree as cattle. Some of the cattle ranchers who survived economically later invested in sheep. The number of experienced sheep men, however, were few compared with cattle men. “This led to some strange partnerships between the providers of capital and the providers of experience.”

Most enterprises ran on a share basis, and “a man who was ambitious and who could take the loneliness and hardship of herding could get himself in the sheep business often with no capital at all.”[6] Many Norwegian sheep herders belonged to this category and eagerly took the opportunity when it was presented to them. In fact, most Norwegian immigrants who established themselves as sheep owners, started out by being offered sheep on shares, like the pioneer Norwegian sheep rancher and entrepreneur Martin T. Grande.

John F. Bishop and Richard Reynolds belonged to the group of early sheep entrepreneurs. Both men arrived in Montana during the first big gold rush. John Fernando Bishop was born March 14, 1836, in Wyoming County, New York, as the fourth of nine children. After he left home, he first moved to Columbia County, Wisconsin, where he worked in the woods for one year.

Bishop and the first gold rush

In 1860 Bishop took a job as a bullwhacker on a wagon train bound for Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. After his arrival in Fort Leavenworth, he continued to the gold fields at Pike’s Peak, Colorado. When the wagon train arrived in Nevada City on November 1, 1860, he purchased a load of hay, which he sold in small amounts at a good profit. Later that winter he worked in a quartz mill. In spring 1861, he traveled to Atchison, Kansas, to buy supplies. He freighted the load to Colorado, and in summer 1862 he again took up placer mining at Nevada Gulch.

News of the rich gold discoveries in Montana reached the mining districts of Colorado in March 1863. Bishop joined the stampede of men bound for Montana. He arrived at East Bannack on April 20 and sold his team and wagon for $175, and then bought claim No. 3, on Stapleton’s bar. Next spring he sold the claim and moved to Alder Gulch, Virginia City.

Freighting, ranching or mining?

Again, Bishop found that freighting paid better than prospecting. He bought two yoke of oxen and a load of general merchandise in Salt Lake City and returned to Montana with merchandise he sold at a profit of $1,000. In spring 1864 he repeated the cycle: that spring he made four roundtrips to Salt Lake City and back clearing a profit of $5,000.

He did so well that the Fort Benton merchant company I. G. Baker & Co. bought his business in the summer of 1865. Again he started on a new Salt Lake City roundtrip. When winter arrived, nearing thirty, he took up ranching.

Ranching on the Beaverhead River

Bishop established a ranch nine miles north of Dillon in the winter of 1868. Next spring he went into partnership with his friend Richard A. Reynolds (1842 – 1904). Around July 1, the two men set out on a journey to Oregon to buy horses. They drove to Bannack in a wagon driven by a span of horses, crossed the Continental Divide, traveled through Junction, Idaho, and continued to Boise City. The distance from Bannack to Boise City was four hundred miles and not a ranch along the way.

When they reached Umatilla City on the Columbia River in Oregon, they changed direction for the Willamette Valley on the west side of the Cascade Mountains. They crossed the river at the county seat Salem and continued to Portland. Bishop brought with him gold dust and paid seventy-five cents in gold dust for a dollar. They found the prices asked for horses too high. Instead, they used the cash they brought with them to buy 1,500 sheep for 2.50 dollar a head on a ranch three miles from Dalles. Bishop bought 1,100 ewes and Reynolds bought four hundred.

From horses to sheep

They began moving the flock of sheep in the direction of Montana on August 1. It took them three months to move the herd to Montana, not least because the flock had to ford so many rivers and creeks.[7] On November 7, 1869, they were back in Bannack.[8] The distance from the Dalles to Bannack was eight hundred miles and the drive took eighty days.

The flock became the foundation for the first permanent sheep ranch established in the Beaverhead Valley near Dillon. The sheep wintered on the ranch of John Selway, but were driven to the Bishop ranch on the Beaverhead next spring. The sheep were sheared there, but it was hard to get “men who knew how to shear or were willing to do it. We paid fifteen cents a head.” The first wool clip was sold for nineteen cents per pound to Colonel Charles A. Broadwater, owner of the large Diamond R freighting company. The wool fleeces were hauled more than three hundred miles overland south to Corinne, Utah, where they were loaded on a train and transported east to St. Louis.[9] During the next years Bishop and Reynolds built up one of the best-known sheep ranches in Montana. They also raised high grade Durham and Hereford cattle as well as Norman horses on the ranch.[10]

Pointdexter and Orr – another pair of early ranchers

William Crosby Orr was born in County Down, Ireland, on April 11, 1829, and died May 11, 1901, in Beaverhead County, Montana. He was of Scottish heritage and his father was a manufacturer of potash in County Down. The family emigrated to the United States in 1833 and settled in Ohio. William Crosby was number eight of nine children.

His father died when he was only eleven years old, and he had to take responsibility for his own life. In Wheeling, West Virginia, he learned the skills of a carriage maker. At the age of fourteen he moved to Vicksburg, Mississippi, to complete his training. In 1850, seventeen years old, he purchased the woodworking department of the shop where he worked, and in 1853 he also took over the blacksmithing department.[11]

Because of health problems Orr sold his business in 1853, purchased a band of cattle and horses, and joined a wagon train consisting of five families bound for California. In October 1853 he arrived in the Shasta Valley in northern California. Shasta County was organized in 1850, two years after Pierson B. Reading discovered gold on Clear Creek. A small settlement grew up around the discovery site, named Reading Springs. It was renamed Shasta in 1851 and became the county seat.

Friends in California first

Other mineral discoveries followed the first gold rush. In 1853 a local newspaper proclaimed that every river, creek, gulch, or ravine in Shasta County contained gold. Orr established a ranch there in 1854 and let his stock roam free, while he joined the gold miners on the Virginia Bar on the Klamath River.[12] Over time the mining work proved detrimental to his health, and he returned to his ranch.

Phillip H. Pointdexter bought an equal interest in the Orr ranch in 1856 and the joint venture became known as Pointdexter and Orr. Pointdexter was born September 5, 1831, in Danville, Pennsylvania, and died in 1891.[13] His family moved to St. Louis after the death of his father in 1848. In 1852 Pointdexter traveled west across the plains to California. He was involved in mining on the Humbug River, but like so many others he found that money could also be earned by supplying the miners with food and equipment. He opened a butcher shop in Yreka, California. It was here that he met William C. Orr.

A deep friendship developed between the two men. The partnership lasted the rest of their lives. They chose as their cattle brand the Masonic emblem the Square and Compass. This was the first registered brand in California. Later it became the first registered brand in Montana. Both Orr and Pointdexter were Masons and Knight Templars.[14]

The Great California Flood in 1862

Pointdexter and Orr, along with thousands of others, were strongly affected by the Great Flood between December 1861 and January 1862. It was the largest flood in recorded history in Oregon, Nevada, and California and began after weeks of rain and snow in November 1861 and then continued into January 1862.

The Great Flood reached from the Columbia River southward in western Oregon and continued through California to San Diego. Furthermore, it extended as far inland as Idaho, Nevada, Utah, and Arizona. Streams and rivers rose to great heights, flooded the valleys, swept away towns, water mills, dams, flumes, houses, fences, and livestock. The floodwater carried away or destroyed one home in eight.

In all, one-quarter of California’s estimated 800,000 cattle were killed in the flood. In March 1862, the California Wool Growers Association reported that 100,000 sheep and 500,000 lambs had been killed by the floods. Approximately one-quarter of real estate in California was destroyed, and the State of California went bankrupt.

Heading to Idaho and Montana’s gold fields

Poindexter & Orr suffered a heavy loss in the Shasta Valley. Afterwards they moved some of their business to Lewiston where Orr became involved in supplying the growing community with logs. He soon continued to Oregon where he took up mining again. Orr drove cattle to Canyon City in 1863, while Poindexter remained on the original ranch. Next spring, Orr drove cattle to Idaho City.

When the news of the large mineral discoveries at Bannack, Montana, reached them, Orr put together a herd of cattle and drove it to Montana. After crossing the main range in November, the herd was hit by a snowstorm. On his arrival in Bannack, he chose to winter his cattle there, and drove them into the Beaverhead Valley. They wintered well. As a result Orr returned to California in spring 1863 and moved another herd to the Beaverhead.[15]

In 1867, Orr bought another herd of 400 cattle in Oregon and brought them to the Montana ranch. Pointdexter and Orr decided to move their whole business to Beaverhead County, Montana. They sold everything they still owned in the Shasta Valley and moved north via Canyon City, Oregon, before turning east to their ranch ten miles south of Dillon.

According to the History of Montana, 1739-1885, William C. Orr went back to California in 1870 and brought with him a band of 2,700 sheep and 375 horses to Montana. In America’s Sheep Trails. History and Personalities, Edward Norris Wentworth argued that this happened in 1871, and that Orr brought 2,467 California sheep to Blacktail Deer Creek in Beaverhead Valley near Dillon.[16]

German sheep ranchers – the Sieben brothers

Henry Sieben (1847–1937), born in Abenheim in the German state of Hesse Darmstadt, was one of the early sheep ranchers in Montana who had his base in Meagher County. He was the youngest of six children and emigrated with his parents to Chicago in 1852. His mother died one year after their arrival, and the father moved west with his children to Rock River near Crandall’s Ferry, Whiteside County, Illinois. The area was known as Dutch Bottom. In 1856 their log cabin burned to the ground. The children survived but were scattered and placed to live with friends of the family and work for them. Most of the children were already on their own when their father died in 1859.

In April 1864, at the age of 17, Henry Sieben joined his three year older brother Leonard. They moved west through Iowa, crossed the Missouri River at Council Bluffs, and then traveled northwest along the North Platte River. At Fort Laramie they joined a wagon train bound for Montana. It consisted of more than one hundred wagons and was led by John Bozeman.

Cattle ranching and freighting

During his first summer in Montana, Henry Sieben worked for some ranchers in the Madison Valley and the next season he worked as a freighter. The next five years Henry and Leonard were freighters “hauling merchandise brought by steamboat to Fort Benton and by the railroad to Corinne, Utah, into the Montana mining camps.”[17]

The Sieben Brothers bought about ninety head of worn-out oxen from other freight outfits in fall 1869. They nursed them through the winter and next spring sold the fattened cattle to a butcher at Fort Benton. The two brothers started as ranchers at a winter camp in the Lower Smith River Valley in Meagher County in the fall of that year. They bought cattle in northern Utah and herded them to the Smith River Valley.

Sheep ranching from 1874

Their youngest brother Jacob arrived in Meagher County in 1872. He became interested in sheep and in 1874 he was sent to Red Bluff, California, where he bought 2,200 head of Merino sheep. In spring 1875 he began trailing the sheep the 1,500 miles north to Montana. It took months, and in early December he arrived in the Prickly Pear Valley just north of Helena.[18]

The partnership between the three Sieben Brothers was dissolved in 1879. Leonard moved back to Illinois to get married, and he settled in Henry County. Both Jacob and Henry stayed in ranching, but divided their stock. Jacob took over the sheep, while Henry kept the horses and cattle herd and moved his headquarters to the Lewistown area. Over time Henry Sieben became the owner of several ranches under the umbrella of the Sieben Livestock Company. From 1907 he managed his cattle and sheep businesses from his home in Helena.

Credits

Images from the mining towns: The museum displays were photographed in 2018 by Inger Kari Nerheim. For historic images, visit https://virginiacitymt.com. Other images (c) Inger Kari Nerheim.

All tables are compiled by Gunnar Nerheim for this publication.

Notes

1 Edward N. Wentworth, “Eastward Sheep Drives from California and Oregon”, The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, vol. 28, No. 4, March 1942, pp. 507-538.

2 K. Ross Toole, Montana. An Uncommon Land, Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 1959, Fourth Printing March 1968, p. 148.

3 Wentworth, “Eastward Sheep Drives from California and Oregon”, The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, pp. 507-538, p. 508; L. G. Connor, A Brief History of the Sheep Industry in the United States”, Agricultural History Society Papers, vol. 1, 1921, pp. 89,91, 93-165, 167-197; Harold E. Briggs, “The Early Development of Sheep Ranching in the Northwest, Agricultural History, Vol. 11, July 1937, pp. 161-180; Judith Keyes Kenny, “Early Sheep Ranching in Eastern Oregon”, Oregon Historical Quarterly, Vol. 64, No. 2, June 1963, pp. 101-122.

4 Ross Toole, Montana. An Uncommon Land, pp. 149, 152.

5 Wentworth, America’s Sheep Trails, p. 263.

6 “Beginning of the Montana Sheep Industry. As Narrated by John F. Bishop”, The Montana Magazine of History, vol. 1, April 1951, pp. 5-8.

7 Wentworth, America’s Sheep Trails, pp. 295-296.

8 “Beginning of the Montana sheep Industry”, The Montana Magazine of History, vol. 1, April 1951, p. 8; Progressive Men of Montana, A. W. Bowen & Co, Chicago, p. 52.

9 Progressive Men of Montana, p. 346.

10 Michael A. Leeson, History of Montana, 1739-1885, Chicago 1885, p. 993.

11 History of Beaverhead County, 1990, p. 447.

12 Montana. The Magazine of Western History, volume 20, no. 1, Winter 1970, p. 83.

13 Michael A. Leeson, op. cit., p. 993.

14 Leeson, op. cit., p. 993; Wentworth, America’s Sheep Trails, p. 260.

15 Dick Pace, “Henry Sieben”, Montana. The Magazine of Western History, Vol 29., No. 1, January 1979, pp. 2-15, p. 4.

16 Pace, “Henry Sieben”, p. 6; Wentworth, America’s Sheep Trails, p. 297.