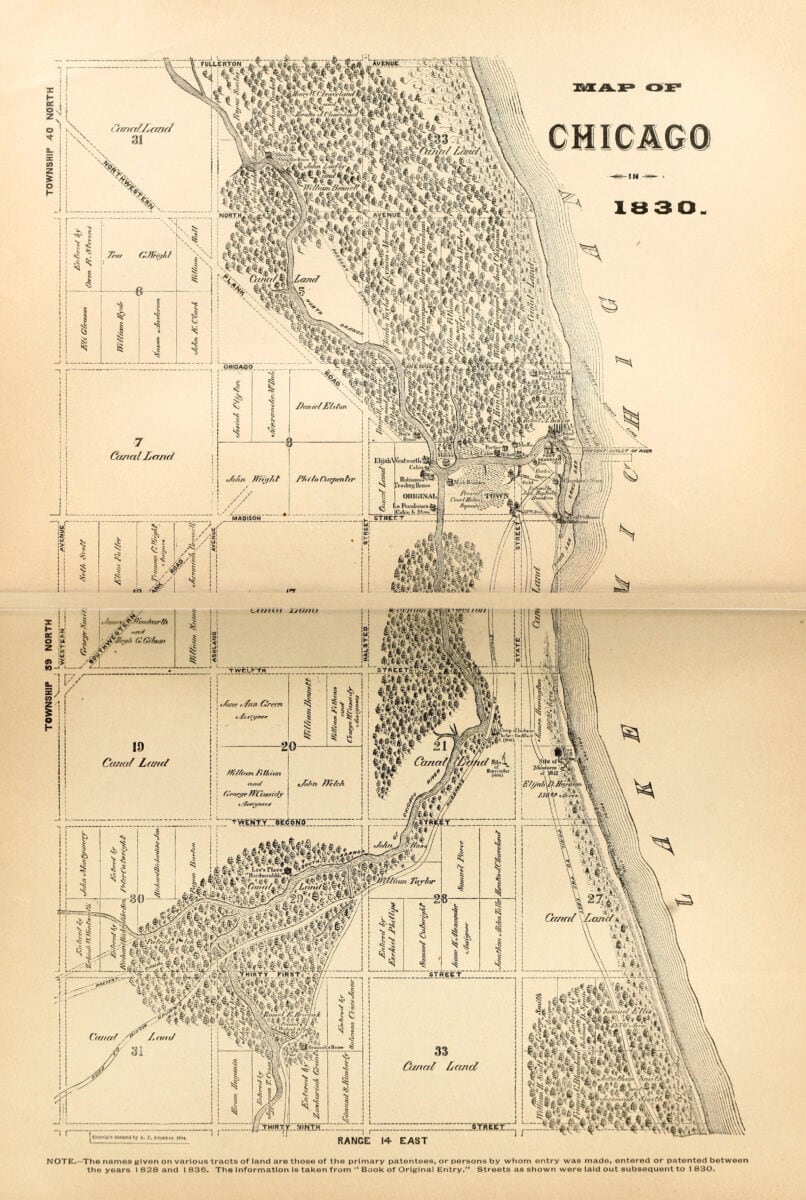

Cleng Peerson set out on a long journey in spring 1833, looking for better land further west. He traveled to Ohio, across Michigan, and through northern Indiana into Illinois He continued along the shore of Lake Michigan as far north as present Milwaukee. Then he returned to Chicago and walked southwest until he reached La Salle County. He liked the land very much. When he returned to the Norwegians in the woods in Western New York, he strongly recommended that they break up from their farms on the Pulteney Estate and go west to La Salle County. The map of Chicago from 1830 shows streets and buildings. When Cleng Peerson passed through in 1833, he saw a “small village”. But the streets for a greater city were laid out as early as in in 1834.

His “glowing reports on conditions in the West found ready acceptance among the New York colonists.” The first six Norwegian families moved to La Salle County, Illinois, in 1834. Their move marked the beginning of the second Norwegian settlement in the United States, known as the ‘Fox River Settlement’.[1]

Why did Peerson go?

Did the Norwegian immigrants in Western New York ask Peerson to find better land for them? The classical books of the Norwegian-American historian Theodore C. Blegen, published in 1931 and 1940, are still among the best any Norwegian-American historian has written about Norwegian immigration. Blegen admitted he had no primary sources to prove that the Norwegian immigrants in Western New York asked Peerson to go west.

In 1938 another excellent Norwegian-American historian, Carlton Qualey, assumed that the characteristic feeling of restlessness seemed to have possessed Cleng Peerson, “reinforced by a conviction that western New York was perhaps not the most desirable place in America for Norwegian settlement.”[2]

The best known and most romantic version of why Peerson chose Fox River and La Salle County was presented by the Norwegian-American newspaper editor Knud Langeland. Cleng Peerson returned to Norway in 1842-43 and met several groups of people interested in emigration. Langeland was present at one of these meetings. He later printed the story. After days of walking west-southwest from Chicago, Peerson finally came to a hill overlooking the Fox River Valley.

“Almost dead of hunger and exhaustion as a result of his long wandering through the wilderness, he threw himself upon the grass and thanked God who had permitted him to see this wonderland of nature. Strengthened in soul, he forgot his hunger and sufferings. He thought of Moses when he looked out over the Promised Land from the heights of Nebo, the land that had been promised to his people.” Since Langeland was a prospective settler, Blegen commented in a footnote, Peerson likely told the story the way he did to give the listeners a positive picture of America. Nevertheless, Langeland’s story became the main source for numerous accounts of what since has been known as “Cleng Peerson’s dream”.

Did Joseph Fellows point Peerson west?

The Pulteney Estate had allowed its sub-agent in Western New York, Joseph Fellows, to speculate in land on his own account for years. In the early 1830s he knew that the best land deals in the future would be done in the Midwest. Among Norwegian-American historians J. Hart Rosdail argued that Peerson might have followed the advice of Joseph Fellows. In his book The Sloopers. Their Ancestry and Posterity, published in 1961, he discussed some reasons why Peerson made his exploration trip in 1833. He might have been sent by the Sloopers or in response to his “own well-recognized urges to explore the country; or he may have been sent by the Quaker land agent, Joseph Fellows.”[3] A closer study of the activities of Joseph Fellows and his extended family confirms the close connection between Fellows and the decisions and behavior of Cleng Peerson.

Fellows` political contacts

Fellows had excellent contacts with leading politicians and investors. He was well acquainted with the political debates concerning land sales in the Congress and Senate.[4] When Andrew Jackson was elected President of the United States in 1828 it was a political earthquake. Jackson and his supporters worked towards greater democracy for the common man, known as “Jacksonian Democracy”. Voting rights should be extended to all white men, and Jackson worked hard to end the “monopoly” of government by elites. He and his followers strongly believed in the concept of manifest destiny; that white Americans should settle the American West from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific. Westward lay freedom; eastward lay old Europe.[5] The West should be settled by yeoman farmers, men who owned and farmed their own land.

Joseph Fellows was aware that the policies introduced by Andrew Jackson would have a negative effect on the profits of the Pulteney Estate and many land projects Fellows was involved in. The planning of the Michigan and Illinois Canal from Chicago to Ottawa in La Salle County had already progressed far. When construction work got under way, land prices would increase on both sides of the canal.

Fellows had known Cleng Peerson since 1824

Peerson was an intelligent and sharp observer with an uncanny skill in retelling what he observed, Fellows knew. Peerson was not primarily an “advance agent” for fellow Norwegians, but for Joseph Fellows, Rosdail argued.

When the ice broke up on Lake Erie and Lake Michigan in spring 1833, Peerson began his journey west. In southern Michigan he visited the region where Joseph Fellows and other members of his family had speculated in land since the early 1830s. Joseph Fellows and his brother-in-law Joseph Edward Hill had bought large tracts of land in Berrien County. A letter from Hill to Fellows, dated Berrien, October 5, 1837, clearly documents their land speculations. Joseph Fellows had bought land near Goshen for eight dollars an acre. A canal passed through this land, and in 1837 it was worth $50 an acre, Hill reported.

From Milwaukee to La Salle County

Solomon Juneau was still the leading fur trader on the Milwaukee River when Peerson arrived there. What would the prospects for homesteaders be in Wisconsin, Peerson asked him? The region had dense forests and wasmentirely unsuitable for settlement, Juneau answered. Peerson trusted his assessment and returned to the small town of Chicago, with 300 inhabitants. He then continued in a southwesterly direction until he arrived in the recently organized La Salle County.

If Peerson had arrived three years later, he would have found close to 3,000 persons living in Milwaukee. In spring 1835 every steamboat arriving in Green Bay brought speculators from the East. They were either hunting for fertile land, mill sites, waterpower rights, or land for urban centers. Homesteaders followed on the heels of the speculators.[6]

The settling of La Salle County

La Salle County had from the very beginning a strong southern character. It was organized as a county in winter 1830-31, and the first election was held at Ottawa on March 7, 1831.[7] The first settlers in La Salle County, Illinois, had grown up in the uplands of the Carolinas, Virginia, Tennessee, or Kentucky. When they moved on, they went north along the rivers into southern Illinois, and they kept strong ties with New Orleans and the growing steamboat trade on the Mississippi river.[8]

In 1831 and 1832 the settlers found themselves in the middle of the Black Hawk War. Immigration came to a standstill, and many homesteaders retreated further south.[9] Joseph Fellows and other land speculators were convinced that western migration would increase again the moment an Indian treaty was signed. The Black Hawk War treaty was subsequently signed in Chicago on September 26, 1833, where the Indians, as the speculators expected, ceded their rights to roughly 1,300,000 acres of land in northern Illinois. When the news of the treaty became known, a stream of settlers from the northeastern states arrived in La Salle County. Most of the homesteaders settled close to the proposed route for the Michigan and Illinois Canal along the Illinois River.

The Erie Canal and the settling of the west

When the Erie Canal opened in 1825, average traveling time between Buffalo, New York, and Detroit, Michigan, was reduced to two and a half days at a cost of about fifteen dollars.[10] By 1830 the best soil in New England, New York and New Jersey had been taken. Yankee settlers or settlers with Yankee roots constituted the majority of the first settlers in Michigan.[11] Southern Michigan became known as “Greater New England” or Yankee-land. In her book The Yankee West. Community Life on the Michigan Frontier, Susan Gray defined the region as “extending west from New England along roughly longitudinal lines through upstate New York, Ohio’s Western Reserve, the southern half of Michigan’s lower peninsula, northern Indiana and Illinois.”[12]

The first trickle of settlers into the southern Michigan peninsula and the Detroit area began around 1820. In 1825 92,332 acres were sold and in 1831 217,943 acres. Because of the Black Hawk War and cholera epidemics in 1832 and 1834, land sales declined. In 1835 land sales leaped to 405,331 acres and the year after nearly one and a half million acres of land were sold. In the wake of the financial panic in 1837, the land boom busted. Nevertheless, the Michigan population increased from 28,004 in 1830 to 212,267 in 1840, a growth of 658 per cent.[13]

Land speculation in Illinois was as lucrative as in Michigan. Land sales in Illinois increased by 600 per cent between 1834 and 1835 from 354,010 acres in 1834 to 2,096,623 acres in 1835. The Illinois population increased from 157,445 in 1830 to 476,183 in 1840. “Chain migration and group migration ushered many Yankees, other Northerners, and foreigners to Illinois, especially to the northern half – the booming half – stamping that region with unique imprints.”[14]

The first Norwegian settlers arrived in La Salle County in 1834

In the strong westward flowing migration river, the Norwegian immigrants were a small creek. Many other foreigners and New Englanders came through the Chicago gateway upon the prairies.[15] Neither the Norwegians nor many of the other early homesteaders in La Salle County got paper title to the land they settled on in 1833 and 1834. The United States Congress passed pre-emption laws at different times. Claimants who made certain specified improvements, got the exclusive right to purchase the land they had claimed for a minimum price of $1.25 per acre.[16]

The following Norwegians moved from Western New York to Fox River in 1834: the families of Gudmund Hougaas, George Johnson, Jacob Anderson and Andrew (Endre) Dahl as well as Torsten Olson Bjorland, Niels Thoresen Brastad (Nels Thompson) and Cleng Peerson. In spring 1835 came the families of Ole Olsen Hetletvedt (1797-1854) and Daniel (Stensen) Rosdail (1779-1854). Kari Pedersdatter (1787-1846), the widow of Cornelius Nelson, came with her family in 1836. Her brother Cleng had already purchased land for her and her children. The Norwegians mainly settled in the northeastern part of La Salle County, in the townships of Miller and Mission, but some also settled in Adams, Northville, and Serena.[17]

Converting old debts to new resources

Joseph Fellows knew well what each Norwegian settler owed the Pulteney Estate. He helped the Norwegian immigrants get out of their old debts in Western New York, and made it possible for them to start over again in Illinois. When the land office opened in Chicago in June 1835, Fellows was present. He actively helped them register their land. But Fellows also registered a lot of land for himself.

On June 15, Jacob Slogvig registered 80 acres and Gudmund Haukaas 160 acres in Rutland Township. Cleng Peerson registered 80 acres for himself in Mission township on June 17, and 80 acres for his sister Carrie Nelson. On June 25, 1835, Cleng registered another 80 acres of land. In Miller township Gjert Hovland bought 160 acres on June 17, and on the same day Thorstein Olson bought 80 acres, and Nels Thompson (Thorson) 160 acres. Thorstein Olson soon bought another 80 acres, which he sold to Nels Nelson Hersdal on September 5, but bought another 80 acres on January 16, 1836.[18]

Land speculators like Joseph Fellows acquired the lion’s share of the land for sale in 1835. The same month Fellows helped the Norwegians, he registered at least 5,000 acres of land around the Fox River settlement in Illinois in his own name.

The breakthrough for Norwegian emigration

The Norwegian Fox River settlement in La Salle County, Illinois, became the mother colony for thousands of Norwegian emigrants. Letters home to family and friends in Norway had a far more optimistic tone than the ones written from Kendall, New York. They helped build up emigration “pull”. Families and friends in the municipalities and regions in western Norway where the “Sloopers” came from, were smitten with an urge to emigrate. They sold their farms and bought tickets for their families for the emigration journey from Norway to Fox River, Illinois.

The breakthrough for organized Norwegian emigration came in 1836 and 1837.[19] On May 25, 1836, the brig Norden left the city of Stavanger with 110 passengers on board and arrived in New York on July 20. A couple of weeks later, on June 8, the brig Den Norske Klippe left Stavanger with 57 passengers on board, arriving in New York on August 15, 1836.

In spring 1837 another two emigration ships left Stavanger. The bark Ægir arrived in New York on June 11, followed some weeks later by the bark Enigheden, which arrived in New York on September 14, 1837 with 91 emigrants on board, including 23 families.[20] “In size and influence no other group of immigrants in the first generation of Norwegian immigration can compare with the 343 passengers of these four ships that constituted the bulk of the exodus of 1836 and 1837,” Henry J. Cadbury argued.[21]

Between 1836 and 1845 emigration from Norway to the United States spread to nine Norwegian counties. The total number of emigrants remained small; with an average of 620 persons annually. During those years western Norwegians caught “emigration fever”.

A new settlement in Shelby County, Missouri

Cleng Peerson played a crucial role in the establishment of Fox River as the Norwegian mother colony. Because of the many Norwegian immigrants who arrived in 1836 and 1837, Peerson was again asked to scout for new land. This time he traveled south and chose land in Shelby County in northeastern Missouri. A history of Shelby County, published in 1911, noted that “a small colony of Norwegians wandering about the country decided to settle at the headwaters of North River” in 1839.[22]

The first group, however, arrived as early as March 1837. A party of twelve to fourteen persons moved from La Salle County together with Cleng Peerson, Jacob and Knud Anderson Slogvig, and Andrew Simonson. In a letter dated Ottawa, April 30, 1837, John Nordboe wrote that he and his family were now ready to move to Shelby County, Missouri.[23] He had sold his farm in La Salle County in 1836 for $400.

Sugar Creek, Iowa

An immigrant group that came directly from Norway in 1839, also settled in Shelby County. But the chosen land soon proved disappointing. Several Norwegians, including Cleng Peerson, moved north to the recently organized Norwegian colony at Sugar Creek, Lee County, southeastern Iowa. The Mississippi constituted the eastern border of Lee County and the Des Moines River the western border. The Norwegians located at a place that reminded them of home six miles into Lee County. Neither the Shelby County settlement nor the Sugar Creek settlement were any success.

Norwegian settlements in La Salle County and beyond

The Norwegians arrived in La Salle County in 1836 and 1837. A financial crisis broke out in the United States in 1837. The financial panic brought immigration almost to a standstill. The work on the canal in La Salle County was suspended in 1839.

The Norwegians already living in La Salle County tried to help the immigrants who had just arrived as best they could with housing and feeding them. They also gave advice with respect to better opportunities elsewhere – in Illinois, in Wisconsin and Iowa.

By 1850 most Norwegian immigrants preferred to settle in Wisconsin. Groups of Norwegians settled on Jefferson Prairie and Rock Prairie, Rock County, Wisconsin in 1837. Two years later Norwegian settlements were established in Muskego and Koshkonong, Dane County, Wisconsin.

Washington Prairie in Winnishiek County, Iowa, was established in 1845. The first Norwegian settlement in Minnesota was established in Fillmore County in 1853. I challenge other historians far more knowledgeable than I, to write about the first Norwegians in Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota.

Notes and acknowledgments

Map of Chicago from 1830; Copyright Alfred T. Andreas; Public domain; accessed at wikimedia 28.nov. 2023. <a title=”Copyrighted by Alfred T. Andreas, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons” href=”https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1830Mapof_Chicago.jpg”><img width=”256″ alt=”1830 Map of Chicago” src=”https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/db/1830Mapof_Chicago.jpg/256px-1830_Map_of_Chicago.jpg”></a>

[1] Blegen, Theodore C, Norwegian Migration to America, 1825-1860, (Northfield, MN: Norwegian American Historical Association, 1931): pp. 61-62; Blegen, Theodore C., Norwegian Migration to America: The American Transition (Northfield, MN: Norwegian American Historical Association, 1940).

[2] Qualey, Carlton C., Norwegian Settlement in the United States (Northfield, Minnesota: Norwegian-American Historical Association, 1938), p. 22.

[3] J. Hart Rosdail, The Sloopers, Their Ancestry and Posterity (Broadview Illinois: Photopress, 1961).

[4] Gunnar Nerheim, Norsemen Deep in the Heart of Texas. Norwegian Immigrants, 1845-1900 (in press College Station, Texas A&M University Press, 2024), ch. 3.

[5] Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson (New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1966); John William Ward, Andrew Jackson – Symbol for an Age (London: Oxford University Press, 1953); Steve Inskeep, Jacksonland. President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and a Great American Land Grab (New York: Penguin Books, 2015).

[6] Mark Wyman, The Wisconsin Frontier, (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1998), p. 158.

[7] Elmer Baldwin, History of La Salle County. Its topography, geology, botany, natural history, history of the Mound builders, Indian tribes, French explorations and a sketch of the pioneer settlers of each town to 1840 (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1877), p. 87.

[8] Ray A. Billington, “The Frontier in Illinois history”, Journal of the Illinois Historical Society, 43, no 1 (Spring 1950): pp. 28-45.

[9] James E. Davis, Frontier Illinois (Bloomingtom, Indiana: University of Indiana Press,1998), pp 193-198; Mark Wyman, The Wisconsin Frontier, pp. 145-156.

[10] George N. Fuller, “Settlement of Michigan Territory”, The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 2, no. 1 (June 1915): p. 39.

[11] George J. Miller, “Some Geographic Influences in the Settlement of Michigan and in the distribution of its Population”, Bulletin of the American Geographical Society, 45, no. 5 (1913): p. 346.

[12] Susan E. Gray, The Yankee West. Community Life on the Michigan Frontier (Chapel Hill: Univ. of N. Carolina Press, 1996), pp. 1-2.

[13] Miller, “Some Geographic Influences”, p. 332.

[14] Davis, Frontier Illinois, p. 246.

[15] William Vipond Pooley, “The Settlement of Illinois from 1830 to 1850.” Bulletin of the University of Wisconsin History Series 1 (1908): pp. 287-595.

[16] Paul W. Gates, “Tenants of the Log Cabin”, Mississippi Valley Historical Review 49, no. 1 (June 1962): pp. 3-31; Roy M. Robbins, “Preemption – A Frontier Triumph, Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 18, no. 2 (December 1931): pp. 331-349; Paul Wallace Gates, “Southern Investments in Northern Lands Before the Civil War”, Journal of Southern History 5, no 2 (May 1939): pp. 155-185.

[17] Baldwin, History of La Salle County, p. 163.

[18] A. E. Strand, ed. A History of the Norwegians of Illinois (Chicago, John Anderson Publishing Company, 1905), pp. 73-75.

[19] Trygve Brandal, Hjelmeland. Bygdesoge 1800-1990 (Stavanger: Hjelmeland commune, 1994), p. 30.

[20] Stavanger Adresseavis, May 27, 1836; Stavanger Adresseavis, June 7, 1837; Stavanger Adresseavis, October 13, 1837.

[21] Cadbury, Henry J. “Four Immigrant Shiploads of 1836 and 1837.” Norwegian- American Studies 2 (1927): 20-52.

[22] William H. Bingham, General History of Shelby County Missouri (Chicago: H. Taylor & Co., 1911), p. 31.

[23] Arne Odd Johnsen, “Johannes Nordboe and Norwegian Immigration. An ‘America Letter’ of 1837”, Norwegian-American Studies, 8 (1932): pp. 23-28; Einar Hovdhaugen, Frå Venabygd til Texas. Pioneren Jehans Nordbu (Oslo: Det Norske Samlaget, 1975), p. 41.