When the Civil War broke out in 1861 very little economic activity was conducted by people of European ancestry in Montana. Some Indian trade and missionary activity took place. Small agricultural settlements sold their surplus to homesteaders passing through the territory on their way to Oregon. After the gold discoveries became known in the early 1860s, thousands of men traveled to Montana. The journey to Montana was complicated, expensive and time consuming.

Many traveled west by steamboat from St. Louis up the Missouri River as far as Fort Benton, Montana. They continued by stagecoach or wagon to the gold fields in the south of the territory. This route was very time consuming. People also traveled northwest by way of Salt Lake City but had to cross 450 miles of very arid land. Montana could be reached from the west by steamboat up the Columbia River in Oregon and then along overland trails. “Since Montana was not really close to anything of note, the miners were continually plagued by inefficient, seasonal freight service, and, of course, exorbitant prices for any imported commodity.”[1] Freight companies out of Omaha, Nebraska, began doing business with some of the emerging Montana cities in 1863, places like Bannack, Virginia City, Louisville, and Forest City.

Several mining towns became ghost towns when placer gold mining declined. Miners were quick to move in and out of mining camps. On the road between camps, they learned a lot about the Rocky Mountain region. Many men who made money on placer mining, chose to stay in Montana. They invested their money in livestock, agriculture, and trade.[2] Places like Missoula, Deer Lodge, Helena, Bozeman, and Spokane grew in step with the increasing trade.

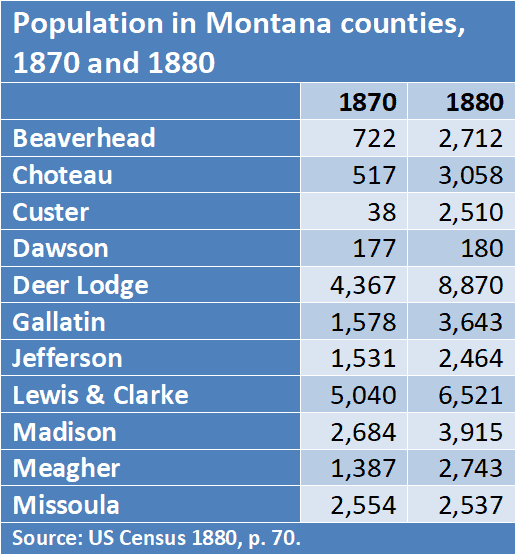

At the time of the US census in 1870, only 20,595 people lived in Montana Territory. The Territory had seven counties and most of them were located in the western and central parts of Montana. The counties with the highest population were dominated by mining.

Norwegian immigrants were also drawn to the Montana gold fields, but they were few in number.[3] Helena became an early mining center and attracted many Scandinavians. In 1870 the highest number of Norwegians and Swedes in Montana lived in Lewis & Clark County (66), Deer Lodge County (43), and Jefferson County (35).

Between 1870 and 1880 the population almost doubled and reached 39,159 inhabitants. In 1880 the highest number of Swedes and Norwegians lived in Deer Lodge County (111), Lewis & Clark County (96) and Jefferson County (49).[4] The best known among the early Norwegian immigrants to Montana was the entrepreneur A. M. Holter. He emigrated from the city of Moss in eastern Norway in 1854 and settled at Alder Creek, Montana, in 1863. After he moved to Helena, he expanded his sawmill business and became one of the richest and most influential citizens of that city.

As in so many other western states, the railroads were the driving force in the settlement of Montana. The Northern Pacific Railroad reached Glendive and Miles City in Eastern Montana in 1881 and Billings in 1882. During the 1880s the population of Montana increased by 265 per cent; 142,924 persons lived in Montana in 1890; 43,096 of them were foreign born.

Among the foreign born in 1890 1,957 had emigrated from Norway, 3,771 from Sweden, and 683 from Denmark. The largest number of Norwegians lived in the counties of Cascade (464), Lewis and Clark (311), and Missoula (207), followed by Silver Bow (167), Park (140), Meagher (111), Custer (106), Deer Lodge (92) and Choteau (88) [5] Many Norwegians settled in the new and growing city of Great Falls in Cascade County. Mining in Deer Lodge and Lewis & Clark counties was still considerable, but by 1890 agriculture and livestock had expanded. A surprising number of Norwegians in Montana were step-by-step migrants from the Midwest, and many of them second-generation Norwegians.

For decades, Norwegian-American historians have been concerned with the different aspects of emigration from Norway, and the transition from a Norwegian to an American pattern of life. The westward movement of Norwegian immigrants within the United States has not been studied to the same degree. The main exceptions from this rule are the historians Carlton Qualey and Kenneth S. Bjork. In his book West of the Great Divide. Norwegian Migration to the Pacific Coast, 1847-1893, published in 1958, Bjork observed that the “many-sided themes of transition from European to American patterns have been carefully examined.” But important research themes such as the movement of immigrants from region to region in the New World had “been largely overlooked.”[6] It was an important aim for Bjork to trace and “interpret the early trek of Norwegian immigrants to the vast stretches of land along the Pacific coast.” This trek was intimately related to and “a result of economic, social, and political developments in the Mississippi Valley.” Bjork concentrated most of his energy on the Norwegian immigrants west of the “Great Divide”, but briefly covered some of the early history of Norwegians in Montana Territory.[7]

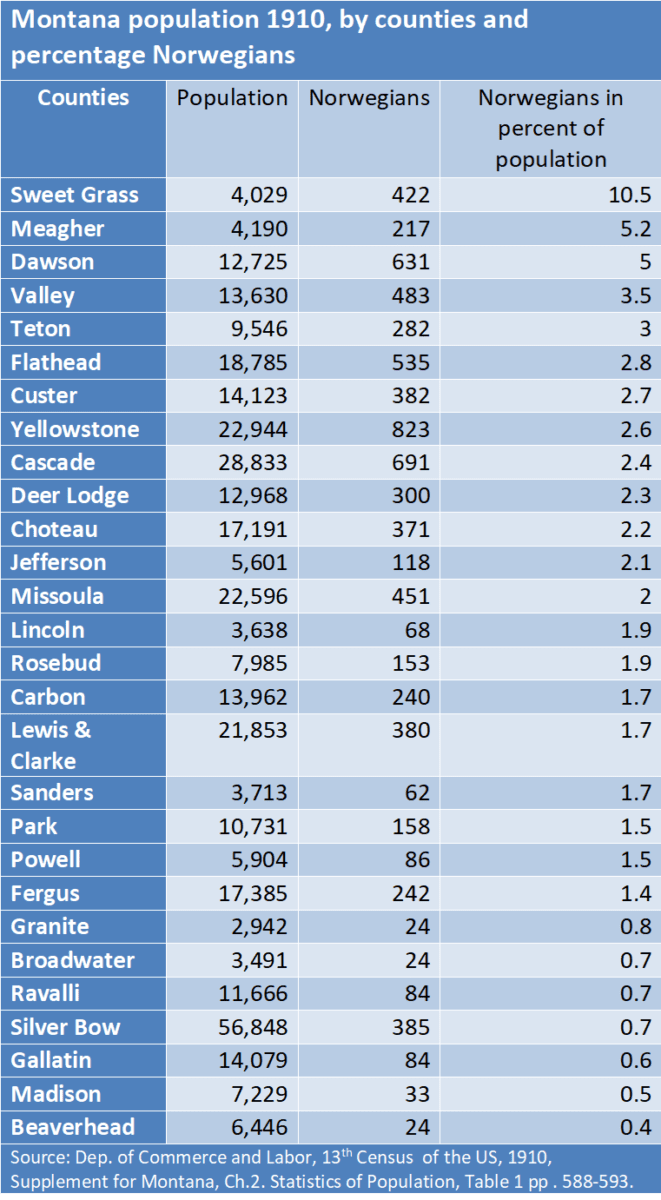

Carlton Qualey discussed the Norwegians in Montana in his Norwegian Settlement in the United States, published in 1938.[8] In the chapter “North Dakota and Beyond”. Qualey discussed how the “Norwegian settlement extended naturally into the eastern counties of Montana.”[9] Norwegians who crossed the eastern boundary into Montana from North Dakota before 1900 often settled in Dawson and Custer counties. Nevertheless, only 371 Norwegians lived in eastern Montana in 1900. Some of them had moved from farms in the Red River districts in eastern North Dakota, and some had emigrated directly from Norway. According to Qualey, the Norwegian element in Montana was never very large, only 1.9 per cent of the total Montana population in 1900 and 5.4 per cent in 1930.

Of the 4,764 Norwegians who lived in Montana in 1900, slightly more than half, 2,487, were born in Norway, 1,228 in Montana, and the others in Utah and states lying to the east. The largest number of Norwegians lived in western and central Montana, in the counties Cascade (including the city of Great Falls), Carbon, Choteau, Deer Lodge, Flathead, Silver Bow (Butte), Sweet Grass and Lewis and Clark (Helena).[10] Most of the Norwegian settlers lived in or around cities and mining communities. By 1930 the Norwegians in Montana numbered 29,387. About a third of them lived in agricultural counties in the northeast.

The Great Northern Railway brought many Norwegians to northern Montana

On January 6, 1893, the last spike on the Great Northern Railway was driven at the west portal of the Cascade Tunnel. The first trains began to run a month later, but the first passenger train did not leave St. Paul, Minnesota, for the Pacific Coast until June.[11] The Great Northern Railway opened a whole new region for homesteaders in northern Montana. The railway bought its lands from the federal government. It received no land grants. The land was resold to single farmers. The Great Northern operated sales agencies in Germany and Scandinavia and subsidized the travel expenses for families.

After 1900 many Norwegian immigrants settled in the counties along the Great Northern Railway line – from Sheridan County in the east, just across the North Dakota border, through Daniels, Valley, Phillips, Blaine, Hill and Liberty counties further west. Between 1900 and 1920 an increasing number of Norwegians also settled in the counties along the eastern border of Montana – in counties like Roosevelt, McCone, Richland, Dawson, Prairie, Wibaux, and Custer.

“By 1930, the Norwegians in these counties, including both foreign- and American-born persons, numbered at least 11,168. Within the boundaries of the United States, the settlements in northeastern Montana form the northwesternmost point to which the Norwegians advanced in their march from the southern tip of Lake Michigan.”[12]

It is very rare to find Norwegians working as cowboys in Montana. In the sheep industry, however, Norwegians participated actively, mainly as sheep herders, but also as sheep owners. The Norwegian immigrant Martin T. Grande was the pioneer and trailblazer among Norwegian sheep owners in Montana. Norwegian immigrants were hired in sheep ranching in Meagher and Sweet Grass counties in Central Montana in the 1880s and 1890s. Around 1900 several of them found new opportunities in Carbon and Stillwater counties further south. Very often they had worked as sheep herders for Martin Grande and others before striking out on their own.

[1] William E. Lass, From the Missouri to the Great Salt Lake. An Account of Overland Freighting, published by the Nebraska State Historical Society 1972, p. 131.

[2] S. J. Coon, “Influence of the Gold Camps on the Economic Development of Western Montana”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 38, October 1930, pp. 580-599.

[3] Kenneth S. Bjork, West of the Great Divide, Northfield 1958, p. 622.

[4] Oscar Melvin Grimsby, “Contribution of the Scandinavian and Germanic People to the Development of Montana” (1926), Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professionals Papers. 5349. http://scholarworks.umt.edu.etd/5349, p. 75-76.

[5] Oscar Melvin Grimsby, “Contribution of the Scandinavian and Germanic People to the Development of Montana” (1926), Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professionals Papers. 5349. http://scholarworks.umt.edu.etd/5349, p. 76.

[6] Kenneth S. Bjork, West of the Great Divide, Northfield 1958, p. vii.

[7] Kenneth S. Bjork, West of the Great Divide. Norwegian Migration to the Pacific Coast, 1847-1893, Norwegian-American Historical Association, Northfield, Minnesota 1958, p. vii. [8] Carlton Qualey, Norwegian Settlement in the United States, Northfield 1938.

[9] Carlton Qualey, Norwegian Settlement in the United States, Northfield 1938, p. 170.

[10] Carlton Qualey, Norwegian Settlement in the United States, Northfield 1938, p. 195.

[11] Albro Martin, James Hill and the Opening of the Northwest, Minnesota Historical Society Press, St. Paul, Minnesota 1976, p. 392-398.

[12] Carlton Qualey, Norwegian Settlement in the United States, Northfield 1938, p. 171.