From the end of the American Civil War and until the economic bust in 1893, European immigrants chose to settle in the Midwest and the Northwestern parts of the United States. Even emigrants in Canada preferred the United States during those decades. At least 1.8 million Canadians moved south across the border into the United States between 1850 and 1900. The largest exodus from Canada occurred between 1875 and 1885. According to United States census records Canadians constituted around 10 to 11 per cent of all foreigners in the United States between 1880 and 1900.[1]

Two massive settler booms in the US, 1865-1873 and 1878-1893

The 1880 US Census listed 181,729 Norwegians as living in the United States. “New Norway” was geographically concentrated within an area extending from Lake Michigan westward into the Dakotas and to the Missouri river. An irregular line from Chicago westward to Sioux City marked the southern border. “Within these boundaries eighty per cent and possibly more, of all Norwegians who have come to the United States have found their homes,” wrote Laurence M. Larson in 1937.[2]

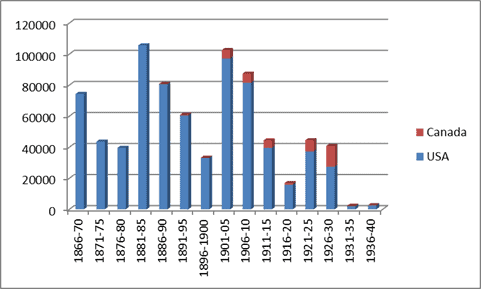

Emigration from Norway to the United States and Canada 1866-1940.

Historical statistics, Statistics Norway.

A peak number of Norwegian immigrants arrived in the United States between 1880 and 1885, a total of 105,645. They were followed by another 80,665 Norwegian immigrants between 1886 and 1890. Norwegian emigration to the United States leveled off somewhat in the 1890s, especially after the 1893 economic depression set in.

Norwegian immigrants were latecomers to Canada

Before 1900, only a trickle of Norwegians chose to settle in Canada. Many Norwegians traveled on Norwegian sailing ships and disembarked in Quebec between the 1850s and the 1870s, but most of them continued to the United States on rivers and lakes to Chicago and beyond. According to Norwegian census data only 606 Norwegians emigrated directly from Norway to Canada between 1891 and 1900.

After 1900, however, larger number of Norwegians chose to settle on the Canadian prairies. Between 1901 and 1905, 5,411 Norwegians emigrated directly to Canada, followed by 5,969 between 1906 and 1910. Norwegian emigration to the United States declined considerably between 1911 and 1915, while direct emigration to Canada held up well with 4,816 emigrants. During the last years before World War I more than one in ten emigrants to the North American continent chose Canada. Most of the Norwegian immigrants ended up on the Canadian prairies as part of the migration stream to western Canada and the Last Best West.

During the First World War Norwegian emigration to North America came more or less to a standstill. Norway was politically neutral during the war and the country experienced an economic boom, even though the problems of importing necessary consumer products from abroad became fairly severe towards the end of the war. During the war and until 1920 less than one thousand Norwegians emigrated to Canada; most of them emigrated in 1919 and 1920.

The economic depression hit Norway in fall 1920

Emigration accelerated again. Between 1921 and 1925 a record 7,217 Norwegians emigrated to Canada, followed by a new record of 13,492 between 1926 and 1930. After the economic crash in 1929, and the international depression which followed in its wake in the 1930s, emigration from Norway to both the United States and Canada fell to very small numbers. Hardly more than 300 persons emigrated to Canada during the 1930s. Return migration was significantly higher.

We know too little about Norwegian settlements on the Canadian Prairies

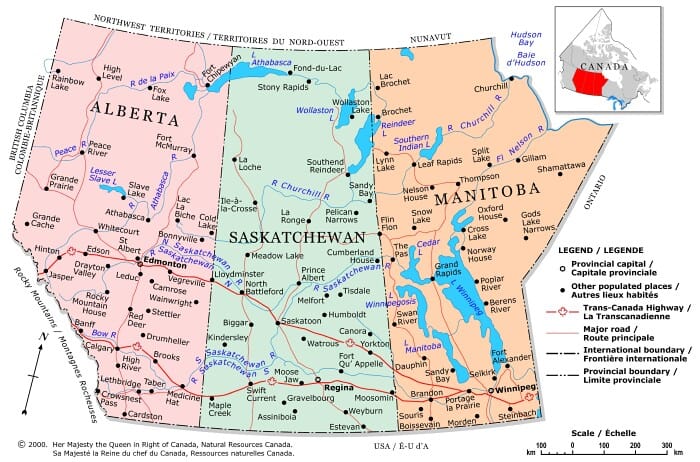

Despite more than a hundred years of historical research on Norwegian immigrants in the United States, relatively little is known about early Norwegian immigrants in Canada. According to the Canadian census of 1916, Norwegians constituted the fifth largest non-native English speaking population group in the prairie provinces. More Norwegians lived in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta than immigrants with a Danish, Dutch, Jewish, Polish, Ukrainian, or Swedish background.[3] Needless to say, we need more knowledge about the settling of Norwegian immigrants on the Canadian prairies.

The Canadian west, Paul Sharp observed, was “the last advance in the long march that had begun on the Atlantic seaboard”. It was far more than the flight of a few disenchanted or restless frontiersmen, but rather a movement that was driven by “a desire for cheap land, the same desire that had activated the earlier agrarian waves to the south.”[4]

The establishment of the Dominion of Canada

The provinces Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia joined in the Dominion of Canada in 1867. King Charles II of England had awarded Rupert’s Land to the Hudson’s Bay Company as early as 1670. Rupert’s Land included the future prairie provinces Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. The area was dominated economically by the fur trade until 1850. After the Dominion of Canada bought Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1869, it integrated the vast area of the North-Western Territory and Rupert’s Land into the Northwest Territories and the province of Manitoba. Prince Edward Island and British Columbia on the Pacific decided to become part of the Dominion between 1870 and 1873.[5]

During the summer of 1873 the boundary between the United States and Canada was staked out from the Lake of the Woods toward the east to Waterton Lakes in the west. The Canadian government established the Northwest Mounted Police that year.[6] Its first assignment was to enforce Canadian authority along the new border, and to control and regulate the whisky trade between white Montana traders and Indian tribes on the Canadian side.[7]

The first police post in Alberta was established at Fort MacLeod in 1874. In 1875 the government strengthened its position further north by building a second police fort at the junction of the Bow and Swift Rivers, where the grasslands of the rolling plains gave way to the forested foothills of the Rocky Mountains. This fort was named Calgary and became an important stop on the Old North Trail linking Fort Benton on the Missouri river in Montana with Fort Edmonton on the North Saskatchewan River.[8]

As early as 1870, the Canadian province of Manitoba was established as a federal province, while the provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta further west were established in 1905. The three prairie provinces covered the area bounded by the United States to the south, the Canadian Shield in the east and the Rocky Mountains in the west. The 60th parallel marked the northern boundary. Saskatchewan and Alberta together covered a larger area than France or Germany. Manitoba was nearly twice the size of the combined areas of Belgium, Holland, and Denmark.

Cattle ranching in Palliser’s Triangle before the farmers arrived

The buffalo was extinguished on the open prairies around 1880. In Canada the Indian tribes accepted to live on specially assigned reserves more willingly than the Indians in the United States. The grass on the land the buffalo had used on the Canadian side of the border proved to be excellent for cattle ranching. During the 1880s huge herds of tough, long-horned cattle were driven across the border from Montana into Alberta and Saskatchewan. They grazed on millions of acres of open land, with no farmers and no fences.[9] As the first farmers began to arrive in greater numbers in the 1890s, they came into conflict with the ranching interests.[10]

Railroads, people and politics

The Dominion Government argued that the population growth in the Prairie Provinces was crucial to the transcontinental political integration of Canada. When British Columbia joined the Confederation in 1871, the Dominion government promised the new province that a transcontinental railway would be built within ten years. The proposed line, 1600 km longer than the first transcontinental railway line in the United States, would represent an enormous investment for a nation with a population of only 3.5 million people.

Two syndicates competed hard for the contract. The contract was secretly awarded to Sir Hugh Allan in return for financial support for the Conservatives during the election in 1872. It was later revealed that American railroad interests were the principal backers behind the Allan consortium. These interests financed the Conservative election campaign with 350 000 dollars.

After the news became public, the government had to resign. The political scandal led to delays in the building of the transcontinental railroad for almost a decade. Finally, on February 15, 1881, the Canadian Pacific Railway Act received Royal Assent. The government would pay the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) a subsidy of $25,000,000. In addition, the company would also be awarded 25,000,000 acres of land. After the railway was completed, the government would award the CPR a monopoly for 20 years.

The importance of the Transcontinental Railroad

The building of the CPR came to have a long-term impact on the settlement of the prairie west. It also influenced the growth of several cities along the line, such as Winnipeg, Calgary, and Vancouver.[11] The last spike on the eastern section of the Canadian Pacific Railway was driven on May 16, 1885, on the north shore of Lake Superior.

On August 10, 1883, the first train reached Calgary on the Bow River. The last spike on the railway between Calgary and British Columbia was driven at Craigellachie in Eagle Pass in British Columbia on November 7, 1885. The first train which traveled across Canada from sea to sea arrived in Port Moody at Pacific Tidewater the next day.

Edmonton was the largest city north of Calgary, with a population of 700 in 1892. The city experienced strong growth from 1891 when the Calgary and Edmonton Railway, a subsidiary of CPR, was built north from Calgary to the North Saskatchewan River. Land-hungry homesteaders used this branch railway to get on to the plains of Central Alberta.

Explosive growth after 1900

The population of Edmonton increased from 2600 people in 1901 to 25,000 in 1911. Much of the increase was a result of continued agricultural immigration to the surrounding area. There were some new factors as well; the most important being Edmonton’s designation as capital of the new Province of Alberta in 1906. This decision led to new civil service jobs in the provincial administration. The new University of Alberta was also located to Edmonton.

The population of Calgary increased from 4,398 inhabitants in 1901 to 43,704 in 1911, a growth of 893 per cent in a decade. Both Edmonton and Calgary experienced a real estate boom. When the building boom collapsed in 1913, Edmonton had around 70,000 inhabitants, which dropped below 64,000 inhabitants in 1916. At the peak of the boom in Calgary the population reached a record high of 90,000 inhabitants. Both cities experienced a decline in population during the First World War. The population of Edmonton decreased 8 per cent between 1911 and 1921, while the population of Calgary had a net increase at 12 per cent.

More than one million persons immigrated to Canada between 1900 and 1907, and half of them, 530,000 persons, settled in the North-West Provinces. The populations of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta grew from 419,512 inhabitants in 1901 to 808,863 in 1906.

Around 60 percent of the population growth in the North-West Provinces was a result of migration from eastern Canada. Far more remarkable was the stream of immigrants from the United States, which grew by 336 percent. Canada opened its doors to newcomers from all parts of the world. The number of new settlers from the United States was only 10,000 less than from the rest of Europe. In 1906 people of European origin represented 18 percent of the total population in the North-West Provinces.[14]

Image credit: Political map of the Prairie Provinces, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. (c) 2000 Natural Resources Canada

[1] S. Morley Wickett, “Canadians in the United States”, Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 2, June, 1906, pp. 190-205, p. 194.

[2] Laurence M. Larson, The Changing West and Other Essays, Northfield, Minn. 1937, p. 71.

[3] The Canada Year Book 1918, p. 106.

[4] Paul F. Sharp, “When Our West Moved North”, The American Historical Review, vol. 55, No. 2, January 1950, pp. 286-300, 287.

[5] Robert Bothwell, The Penguin History of Canada, Toronto 2006, pp. 210-213; Philip Buckner, “The Creation of the Dominion of Canada” in Philip Buckner (ed.), Canada and the British Empire, Oxford History of the British Empire, Oxford 2008, pp. 66-86.

[6] Robert Bothwell, The Penguin History of Canada, Toronto 2006, pp. 228-232; Philip Buckner, “The Creation of the Dominion of Canada” in Philip Buckner (ed.), Canada and the British Empire, Oxford History of the British Empire, Oxford 2008, pp. 74-75.

[7] Paul F. Sharp, Whoop-Up Country. The Canadian-American West, 1865-1885, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 1955.

[8] David H. Breen, Calgary: Police Post to Oil Capital, National Museum of Man, Ottawa 1981, p. 1.

[9] Harold E. Briggs, The Development and Decline of Open Range Ranching in the Northwest”, The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 20, No. 4, March 1934, pp. 521-536; Warren M. Elofson, Frontier Cattle Ranching in the Land and Times of Charlie Russell, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, 2004.

[10] David H. Breen, “The Canadian Prairie West and the “Harmonious” Settlements Interpretation”, Agricultural History, Vol. 47, January 1973, pp. 63-75.

[11] J. B. Hedges, The Federal Railway Land Subsidy Policy of Canada, Cambridge, Mass. 1934.

[12] David H. Breen, Calgary: Police Post to Oil Capital, published by National Museum of Man, Ottawa 1981, p. 1.

[13] David H. Breen, The Canadian West and the Ranching Frontier, 1875 – 1922, Ph.D. thesis, University of Alberta 1972.

[14] Ernest H. Godfrey, ”Settlement and Agricultural Development in the North-West Provinces of Canada”, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Vol. 71,No 2, June, 1908, p. 404.